Bridget Young, English and Humanities teacher at The Holmewood School in London, tells us about her class’s rewarding experience using the Collins Readers schools edition of Skulduggery Pleasant in the classroom.

Skulduggery posters had been plastered around the school and in my classroom. The year nine students had many questions about these mysterious posters and little by little, I told them about the book, overstating the macabre.

‘Oh, you wouldn’t want to read that. It’s far too violent and scary.’

After a few days, the students had ‘convinced me’ to let them read it.

Like many teenagers their age, to show such interest in reading a novel is unusual for my students. On top of the regular distractions and reluctance to read, they all have a diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder.

While they are classed as ‘highly functioning’ on the autistic spectrum, encouraging my students to read something that is outside of their usual area of interest, or anything longer than a Facebook comment, can be a challenge.

I knew that if they weren’t engaged from the very beginning and if their interest wasn’t sustained, all manner of behaviours could manifest in the classroom and I would have lost them. They may have even flatly refused to read the book.

However, the students were hooked on Skulduggery right from beginning. The book works for students like mine because the story is fast-paced, with quick-witted dialogue, and while the language is accessible, it doesn’t talk down to them.

The characters are quirky and their interactions are both humorous and heart-warming. The students laughed out loud in parts, and often read the story in class using different voices, which is a real achievement for them in developing their social imagination.

Planning interesting lessons for this unit was easy, with an engaging scheme of work available for free on the Collins Education website.

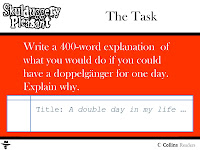

The students enjoyed the assessment tasks, one of which asked them to write about what they would do with a personal clone for a day. A success criterion was included in the resources and the task was mapped to the national curriculum, which made it easy for me to plan and mark.

There are also many online interactive resources for this novel. The students watched interviews with the author, which helped them connect the story with the writing process. There is even an interview with Skulduggery Pleasant himself! This was great stimulus for our speaking and listening task, where the students were asked to hot-seat a character from the novel.

They also enjoyed creating their own Skulduggery Pleasant characters on the ‘character creator’, which is available on the Skulduggery Pleasant official website. They just loved to imagine that they were part of the Skulduggery world.

The first book ends on a cliff hanger, and the students couldn’t wait to read the next book. So we started a lunchtime book club, so that we could read and discuss the second book together.

Other teachers were shocked when they saw a group of year nine students reading of their own volition during their lunch break! Parents have also commented about how engaged in the novel their children are. It has been so rewarding to see the students develop a love of reading through Skulduggery Pleasant.

Bridget Young teaches English and Humanities at The Holmewood School London, which is a school for children with high functioning autism, Asperger’s Syndrome and other specific learning difficulties. She is originally from Brisbane, Australia, but now calls Hackney, in East London, home.