One hundred years ago, in the middle of the First World War, the Battle of the Somme was fought on a twenty-five-mile length of the border between France and land occupied by Germany. Between July and November 1916 over a million soldiers were killed from both sides. For five days before the start of the battle, artillery shells bombarded German positions. During the course of the battle and indeed the whole war, a huge amount of explosive was used. This wasn’t the gunpowder used in the wars of Napoleon or The English Civil War but new high explosives developed by scientists including Alfred Nobel fifty years earlier.

From Gunpowder to Nitroglycerine

Gunpowder consists of charcoal (carbon), sulfur and potassium nitrate, ground together to form a mixture. The powder burns quickly but only becomes an explosive if packed into a confined space such as a cannon or musket. The properties of the mixture were discovered by the Chinese during the first millennium and it arrived in Europe in the thirteenth century. Gunpowder was soon being used in weapons and in mining and quarrying. Gunpowder was deadly stuff but as the canal and railway building booms of the nineteenth century carved their path through the countryside there was a demand for more powerful explosives.

Concentrated nitric and sulfuric acids had been known for centuries but it seems that it was only in the early nineteenth century that the power of the mixture of acids to make explosive materials was discovered. In 1846 Christian Schönbein mopped up a spill of nitric acid with a cotton apron then put it over a stove to dry. He was rather surprised when it burst into flame with a flash. He had invented guncotton.

A year later, Ascanio Sobrero, working at the University of Turin for Prof. Jules Pélouze, discovered nitroglycerine. Glycerine, also called glycerol, is a by-product of the manufacture of soap. Fats and oils react with a strong alkali to produce soap and glycerine. Sobrero found that reacting glycerine with a mixture of sulfuric and nitric acids produced a very unstable liquid. Unless the nitroglycerine was kept in freezing temperatures it decomposed violently. Even a small shake was enough to make it explode and the detonation was fifty times more powerful than with same amount of gunpowder. Sobrero was so scared by his discovery that he told no one about it for a year.

Over the next twenty years, various explosive specialists tried to use nitroglycerine. In the USA where the railroads were pushing through mountainous country there was a need for high explosives. Small amounts of liquid nitroglycerine were produced on site and speeded up the tunnelling process. There were, however, frequent fatal accidents. As a result, the explosive was banned in many places.

Alfred Nobel Sees an Opportunity

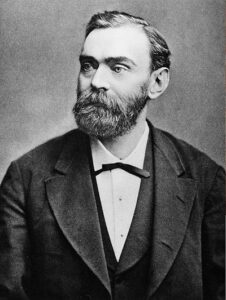

Alfred Nobel was born in Stockholm in 1833. His father, Immanuel, was an inventor but shortly after Alfred was born he went bankrupt. Immanuel moved to Russia where the government showed interest in one of his inventions – a landmine containing gunpowder. In 1842, with the Nobel company doing well, Alfred and his family joined Immanuel in St Petersburg. Alfred and his brothers were taught at home by tutors. While his brothers became engineers, Alfred discovered chemistry. One of his chemistry tutors, Professor Zinin, told Alfred about nitroglycerine.

At the age of 17 Alfred was sent off to travel Europe to increase his knowledge of chemistry. In Paris he studied with Pélouze and Sobrero and learned more about nitroglycerine. He saw that there were possibilities of using the material in his father’s armaments business, if only a way could be found to make sure that the temperamental substance only exploded when required to do so.

Alfred returned to St Petersburg in 1852 and began work with his brothers in his father’s factory. At the end of the Crimean War the Russian government had less business for the Nobel company. In 1859 Immanuel became bankrupt again and returned to Sweden. Alfred remained in Russia with his two older brothers hoping to rebuild the business. Amongst other inventions, Alfred continued to work with nitroglycerine with little success.

In 1863, Alfred returned to Sweden to help his father in a new explosives business. They had a small factory on the edge of Stockholm. There they manufactured small batches of nitroglycerine which Alfred had found could be set off by a small detonator of gunpowder packed in a tube. The problem was still the instability of the nitroglycerine itself. An explosion at the works in 1864 killed his youngest brother, Emil, and caused Immanuel’s third bankruptcy. Alfred was very upset by Emil’s death but he was spurred on to find a way to make nitroglycerine safe.

It’s Dynamite

Late in 1866 Alfred Nobel had the idea of mixing liquid nitroglycerine with a substance called kieselguhr. This is a white, clay-like material found as a natural rock. It is formed from the silica skeletons of microscopic diatoms that lived in the oceans millions of years ago. Because of the shape of the diatoms, kieselguhr has lots of tiny spaces in it so is very absorbent. Nobel found that 1 part kieselguhr would absorb 3 parts of nitroglycerine and form a stable, soft solid that could moulded into shape.

The material would only explode when set off by a detonator based on Alfred’s earlier invention. Alfred called his new explosive, “Dynamite”. Though not quite as powerful as pure nitroglycerine it was much more explosive than gunpowder. It was a high-explosive, but completely safe.

The Nobel company began production of sticks of dynamite in Sweden in 1867 and within ten years it was being manufactured in twelve countries. Mining and construction engineers were delighted to have a safe high-explosive available for blasting through rock. Alfred was delighted with the progress the company made although they met competition from other explosive manufacturers and governments keen to control the production of armaments. Other high-explosives appeared such as gun-cotton, gelignite, TNT and mixtures of ammonium nitrate with various substances, but for most people, dynamite was the high-explosive.

Nobel intended dynamite to be used for peaceful purposes but it was soon used in war. Both the French and the Germans used it in the war they fought from 1870 to 1871. Later Nobel became more involved in developing explosives and weapons for governments but he stated that his purpose was to ensure peace between nations. He thought that if the weapons were so powerful that one army could wipe out another in a day then wars would not happen. He did not foresee the destruction and killing of the First World War that proved him wrong.

The Nobel Prizes

Alfred Nobel’s companies brought him great wealth but he didn’t have his own family to share it with. He was so busy travelling around the world visiting his factories that he never married. At the age of 43 he advertised for a companion. Countess Bertha Kinsky answered his call and they became friends. They were not together for long however, because Bertha married another gentleman. Alfred and Bertha continued to write letters to each other. Bertha became a leading member of the group that was against the arms race that the countries of Europe and America were involved in.

Bertha’s ideas influenced Alfred so that when he wrote his final will he left almost all his money to the funding of the annual Nobel Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology and Medicine, Literature and Peace. Nobel died in 1896 and his will was a surprise to all the relatives descended from his brothers and sisters who expected to inherit his fortune. They fought the will unsuccessfully for five years so the first Nobel prizes were not awarded until 1901. Bertha was awarded the Peace prize in 1905.

Activities

1. Gunpowder is a low explosive, while nitroglycerine is a high-explosive. What is the difference between a low and high explosive?

2. Why do you think dynamite became such a successful product so quickly after its invention in 1866?

3. Alfred Nobel was also interested in literature and writing which is why there is a Nobel Prize for Literature. He wrote poems, a satirical comedy and a tragedy. Find out more about Alfred’s life and interests.

4. 4C3H5O3(NO2)3(l) ⇒ 12CO2(g) + 6N2(g) + 10H2O(g) + O2(g)

This is the equation for the decomposition of nitroglycerine in an explosion. The reaction is very fast and gives out a lot of energy. Explain why the explosion is so powerful.

5. Nitrating mixture (nitric acid + sulfuric acid) reacts with many substances to make explosives. Find out more about the discovery and uses of guncotton, TNT and other explosives.

6. Alfred Nobel thought that making weapons more deadly would make them a deterrent that no government would dare to use. Discuss the evidence for the argument that Nobel was both right and wrong.

7. Discuss whether Alfred Nobel’s discovery and invention of dynamite in 1866 was good or bad for the world.

8. Imagine that you were present at the reading of Alfred Nobel’s will. Describe the reactions to the terms of the will.

Bibilography

The Big Bang – a history of explosives, G.I.Brown, Sutton Publishing 1998

http://www.nobelprize.org/alfred_nobel/biographical/

http://railroad.lindahall.org/essays/black-powder.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitroglycerin (and other explosives)

Photo Sources

Alfred Nobel – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alfred_Nobel3.jpg

Peter Ellis