How do children form their ideas about other peoples and countries? The answer is that they usually draw on a number of different sources. Parents, peers and the mass media will undoubtedly be important influences. Pictures, videos and stories will feed their imagination. Many are stimulated by their interest and empathy for large animals and different habitats. For some children, travel experience and direct contact with foreigners will also be a significant factor.

Teachers can build on these foundations in all sorts of ways. Helping pupils to develop balanced and unbiased images of places beyond their direct experience is an important educational task. It can involve work in many curriculum areas but belongs especially in geography which is pre-eminently about the world and its peoples. Tracing the term ‘geography’ back to its linguistic roots make this point abundantly clear; ‘geo’ means ‘Earth’ and ‘graphia’ means ‘writing’.

The geography national curriculum addresses world knowledge in two rather different ways. Firstly there is a set of requirements relating to place knowledge. At key stage one the focus is on naming and locating the United Kingdom and different continents and oceans. At key stage two place knowledge is extended to include major cities, countries and environmental regions, especially in Europe and North and South America.

The second set of requirements concerns detailed studies of individual places. At key stage one children are expected to learn about a small area (a) in the UK (b) anywhere in the world outside Europe. At key stage two they should study a larger area or region (a) within the UK (b) within a European country and (c) within North or South America.

Why does international understanding matter?

Learning about other people and cultures is an increasingly important part of what it means to be educated today. We live in a globalised world. Many of our goods are imported from overseas, people travel in large numbers to overseas holiday destinations, our economy depends on international finance. This level of international interaction would have been quite unimaginable even fifty years ago.

Perhaps even more importantly we live in a modern multi-cultural society. In the UK today, one person in every eight is from an ethnic minority and about a third of the people living in London was born overseas. The movement of people around the world is one of the striking features of our age and respecting different cultures and heritage is an essential part of building an inclusive society.

These changes in social and economic conditions mean that countries need to collaborate and work together than they did in the past. When it comes to confronting global terror, crime or climate change nations simply cannot be effective if they operate alone. Crime and pollution are not limited by national borders and major environmental issues can only be addressed through international co-operation and agreement.

What are the features of best practice?

Teaching children about distant places isn’t always easy. Differences in wealth and alien customs and beliefs can be hard to explain. There is a danger of creating stereotypes and of imposing our own views and prejudices. Teachers are often advised to start by stressing similarities between places but this tends to make them seem boring. The alternative, starting from differences, is equally problematic because it can lead to ‘othering’ and feelings of superiority.

There are some fascinating research findings about children’s perceptions of distant places. For example, it seems that children’s feelings about countries sometimes emerge in advance of what they know about them. Also, their knowledge varies not only according to their age but also according to their gender, social class, ethnicity and where they live (Barrett 2012). Developmentally, it appears that children go through a period in middle childhood when they relish stories about hunter gatherers and life in prehistoric times. Furthermore, places which are geographically remote or distant also tend to be seen as far away in time and therefore primitive or backward.

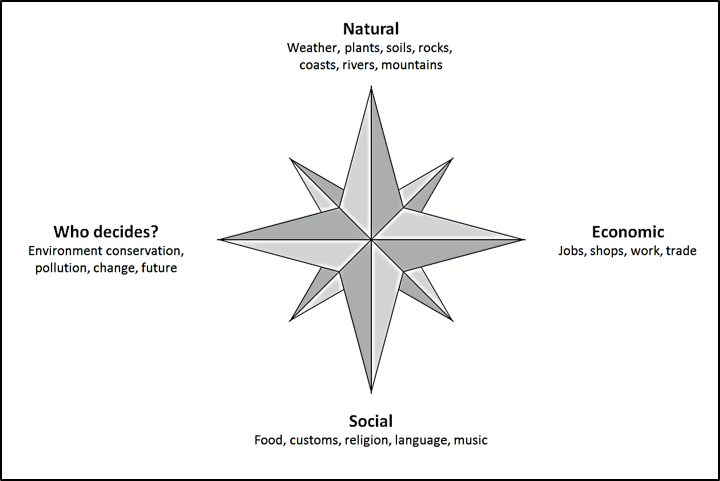

Being aware of these factors is the first step towards constructing your own teaching programme. There are lots of published resources to draw on and huge quantities of information are available on the internet. Schools-linking presents another approach which circumvents any worries about stereotypes and which engages children emotionally with a counterpart overseas. The compass rose is a neat way of ensuring a balanced project (Figure 1). The main point to remember is that whilst the social/cultural dimension is often the most accessible in teaching terms, a geographical study also needs to consider the physical setting and the way in which places are continually evolving and changing.

Pupils who have not engaged with distant place studies as part of their primary school education are liable to have an impoverished view of the world. They will have also have missed out on the opportunity to lay down some of the key foundations for inter-cultural understanding. When they come to assess the quality of teaching in schools Ofsted are now required to report on pupils’ spiritual, moral, social and cultural development (SMSC). Teaching about distant places is not only a key element in the primary geography curriculum, it is also part of pupils’ wider development.

Reference

Barrett, M. (2012) Children’s Knowledge, Beliefs and Feelings About Nations and National Groups, Hove: Psychology Press

Stephen Scoffham

Dr Stephen Scoffham is a Visiting Reader in Sustainability and Education at Canterbury Christ Church University and co-author of the recently published Collins Primary Geography textbook series.

This article was written for Teach Primary magazine (vol.9 No.4) To find out more about the magazine visit www.teachprimary.com