The last twelve months or so have affected many people in many different ways. Apart from the appalling death toll and the long-term effects on the health of many others, the control measures put in place have changed the way that schooling has worked for entire cohorts. The Extended Response Question resource I edited for Collins turned out to be a lockdown publication in more ways than one. Though conceived prior to the pandemic, much of the writing was done during the first lockdown. Although designed for use in a conventional classroom setting, it has much relevance for the situation we now find ourselves in. This article outlines why good literacy is a key skill in science, and how you can help develop your students' extended writing to successfully tackle extended response questions in AQA GCSE Sciences.

Why is literacy important in science?

There is a long and not always easy relationship between science education and the development of literacy skills; extended response questions are probably at the sharp end of this. Should the preparation of candidates to deal with ‘six markers’ be seen as a further burden on students and teachers and one peripheral to the central business of developing scientific knowledge and understanding? Is it seen as a key skill of a scientist to be able to construct a longer explanation? Is it best to simply be pragmatic and accept that it’s there in the exams and is worth a not insignificant number of marks?

One of the hallmarks of the last year has been the high profile given to scientists, some of whom have become regular guests on news programmes and many of whom have acquitted themselves well not only in terms of the grasp of their specialism but also their ability to explain complex ideas. This is not new of course; I would argue that it is part and parcel of being a scientist to be able to construct a longer response. Being able to describe a procedure, compare two different approaches, or evaluate an idea is in the job description.

Furthermore, many teachers have come to realise that getting students to write longer responses has a value that goes beyond simply demonstrating a competence in dealing with that type of question. It shows whether they have understood ideas in more detail, can use key terminology in context and draw ideas together from different parts of the course.

How can I improve my students’ extended responses?

The AQA GCSE (9–1) Extended Response Questions Teacher Response Pack was written to offer teachers a way forward in three main ways:

The first was responding to the immediate situation if there are students in Year 11 who are underperforming and need both practice and guidance. We’ll soon know how these students will be assessed for the purposes of awarding grades this year and items like this may well figure large. For some students, it’s more opportunities (so we’ve included dozens of such questions) and for others, it’s an unpacking of the command words. Because AQA now use the same level descriptors each time a certain command word is used, students can be trained to respond accordingly. An evaluate question needs a judgment, for example, and the candidate who doesn’t include one cannot get full marks.

The second purpose is a more strategic view over the GCSE courses and a desire to integrate the use, both of the questions and ideas, about how to explicitly teach the skills of response over the duration of the course.

The third is to support the view that it needs to be an even longer-term strategy. We progressively develop practical skills and cornerstone concepts such as the particulate model of matter over five years; we should do the same with the skills of constructing longer responses.

The constituent aspects of focusing on key terminology, quality sentence construction, and the organisation of text will serve students well on a number of fronts. What some of our students need is repeated exposure to language and ideas. We need to get them to not only think like a scientist but also to write like a scientist, and that won’t happen in the six weeks prior to an exam.

How can I use this resource with my students?

Twenty years in teaching and almost as many in curriculum development have taught me how inventive and creative teachers are (and have to be) in terms of devising approaches and developing ways of developing student competencies. What we’ve done with this resource is to offer a toolkit. There is a range of materials in there. For each question, there is a model answer that would get full marks and another that would get some of the marks. These are designed to present to students to develop their capacity to recognise improvements. We’ve included commentaries as well, to support teachers to see what examiners will look for.

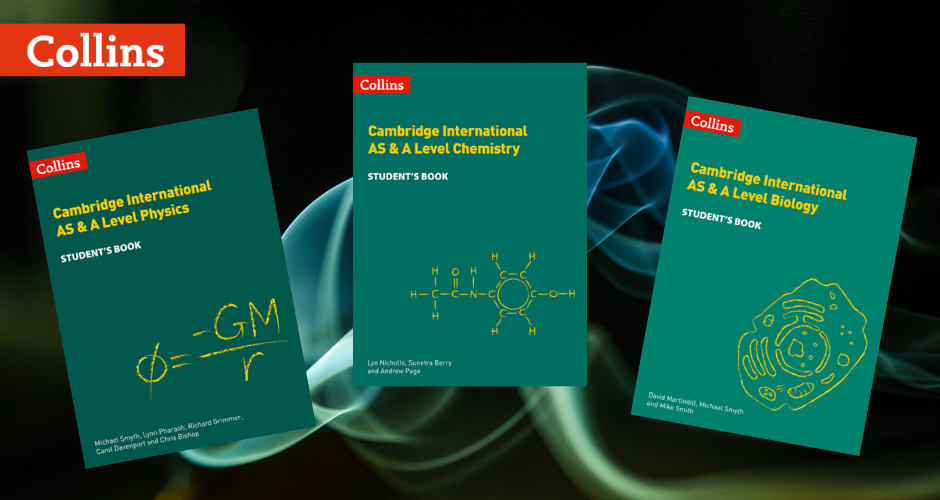

The feedback we’re getting is that this lends itself to use in a range of ways, including learning at home. In a recent interview in the Financial Times, Professor Sir John Holman (author of the Good Practical Science report) expressed the hope that the recently raised profile of science would increase interest in STEM careers, but that this would only happen if, principally amongst other factors, the teaching supported it. Teaching needs to be good, and so do the tools that support it. Check out the sample pages and see what you think.

Watch Ed's talk at the ASE Conference 2021 to find out more about the AQA GCSE (9–1) Extended Response Questions Teacher Response Pack

By Ed Walsh

Ed Walsh is a freelance consultant, specializing in science education. A teacher for twenty years and a team leader for twelve of those, he now writes and edits curriculum materials, designs and delivers CPD, and works with science departments to improve the quality of their provision.

View secondary Science resources from Collins, including books written and edited by Ed.

Read More