There’s plenty of information about the human body that we learn from science and from PE but there are also a lot of questions children ask that go unanswered in the science and PE curriculum. In this set of activities we look at some of the questions about our bodies that children ask and see how we can go about answering them.

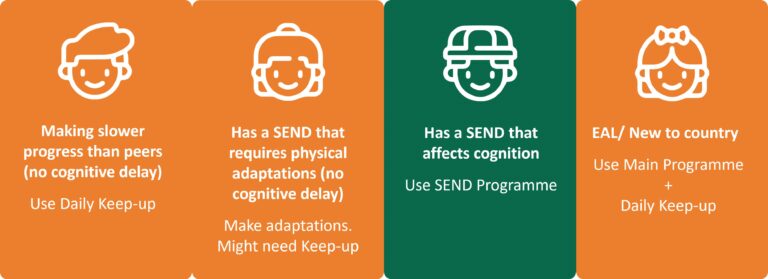

Suitable for: Year 3 to Year 6

Learning Focus:

- Understand some of the processes that help our bodies carry out their daily tasks

- Be able to draw conclusions from the results of experiments

Activity One: How do we keep warm?

There are many ways that the body keeps warm and in this set of activities, the pupils will be able to experience a few.

– Eating food that improves circulation

For this activity you’ll need to check on allergies. First, prepare the foods you’re going to use:

- Grate some root ginger and mix it with some fruit juice.

- Heat up a thick soup

- Make some instant porridge

Choose a cool or cold day for this experiment although it can work on warm days too. Divide the class into three and give one group the ginger juice to try, one group the soup and one group the porridge. Get them to write up the experiment so far whilst waiting for the foods to have an effect. Usually around twenty minutes later they should start feeling warm.

Ask them why they think the ginger juice worked as well as the hot food?

The answer is that ginger has a radical effect on the body’s circulation allowing warm blood from our core to be circulated quickly around our bodies, warming us up.

The soup warms us by putting a warm, thick and so, slowly digested liquid into our core as well as providing some carbohydrate which is converted into energy by the body.

The porridge also warms us from inside but the oats or oatmeal that it is made from has a lot of carbohydrates and continues to warm us as the body turns it into energy.

Feeling chilly? Anyone for ginger porridge then?

– Shivering!

There’s another way our bodies keep us warm when it’s cold and that’s through shivering. When we are really cold, our muscles spasm and the rapid movements burn energy, creating heat.

Activity Two: How do we know what we are eating?

Generally, we ignore the recognition of food by the taste buds on our tongues and instead use visual recognition of food as it approaches our mouths. Our tongues are complex organs which have many thousands of taste buds which detect not only flavours but also the temperature and texture of food and drink. In this experiment, the pupils will get the chance to identify food and drink through taste alone.

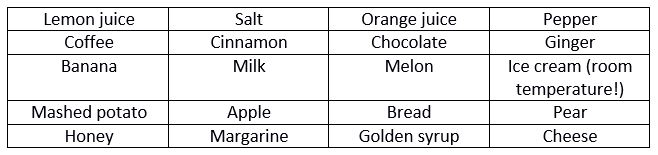

Prepare some food and drink for the pupils to taste. If you’re going to let the whole class try the test you’ll need two sets so there’s no cheating. Beware of allergy issues but use some or all of these suggestions or some of your own…

Put the pupils in pairs and ask one of each pair to wear a blindfold whilst their partner feeds them the food and drink. There will be some incorrect guesses and for these you’ll need to ask the pupils what made them decide it was another foodstuff. For the ones they got correct, how did they know they were right?

Activity Three: How do we stay upright?

This may seem like a silly question but carry out the experiment and you’ll see why it’s not.

Use the school hall and make sure that each pupil has plenty of space around them Put out PE mats for safety then ask the pupils to stand still. You will find that after a minute or so, they will start to lean and wobble and eventually some might stumble or stagger. Ask them to open their eyes and do the same experiment. What made the difference?

The answer is that when we have our eyes open, we can fix reference points around us so we know where we are in relation to the world around us, allowing us to maintain our position. When our eyes are closed, we lose those fixation points and our brain eventually becomes disorientated as it tries to find an invisible reference.

It was long thought that we became dizzy after spinning around because the liquid in our ears became disturbed causing us to lose our balance but it’s now been shown that part of the problem is that in spinning, we also lose the visual fixation points, adding to the disorientation.

Activity Four: How do we judge distance?

There are two ways we judge distance, one by looking at the relative size and distance of objects in our line of vision and the other which can be tested in the following experiments:

Ask the pupils to stretch one arm out pointing their index finger. Now, with their eyes closed, ask them to place their finger on their nose. Many will find that they miss!

Now ask them build a small tower from centimetre cubes on their desk. With both eyes open, ask them to gently touch the top of the tower. Now repeat the experiment but this time close one eye and try to touch the top of the tower. They will find they misjudge the distance, either having to move further forward from where they thought the object was or will knock it over.

The reason why is that, as with hearing, we judge distance and position by using the stereo capacity of our eyes to triangulate an object’s position. If we are missing the use of one of our eyes, we will find it hard to judge the distance.

Activity Five: How do we walk?

This again seems obvious but it’s not until we stop and think about the process that we realise how it works.

The best way to start is to simply get the pupils to walk around the school hall or playground and ask them to think about the process of walking; from starting off until stopping.

Ask them to describe what they did and how it felt in their muscles.

Now video someone walking and, on playback, slow the video down so the pupils can see the process.

They should notice that to start walking they lift and lower one of their legs in front of them before using the muscle in the leg to pull their body towards the position the foot is in and pushing off with the following foot. Usually, to aid this movement, our bodies lean forward slightly. Once the first step is made, our momentum helps the process become smooth and easier.

For a bit of fun, you can ask the pupils to devise a new way of walking a la Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks. From these, ask the pupils to chart the process, including the action of the muscles and body position changes, and whether it makes it easier or more difficult to walk.