What is Bad Science? Well, bad science is when people have misused scientific procedure, such as by cherry picking evidence to prove their case or assuming a causal link by ignoring other factors. However, Bad Science is more than that.

Ben Goldacre is both a doctor and a journalist; he has written a book (Bad Science, published by Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-728487-0), writes a regular column in The Guardian and runs a website. His mission is to track down and expose, amongst others, “credulous journalists misrepresenting good science for the sake of a headline, advertisers, with their wily ways, and good scientists who have passed to the dark side.”

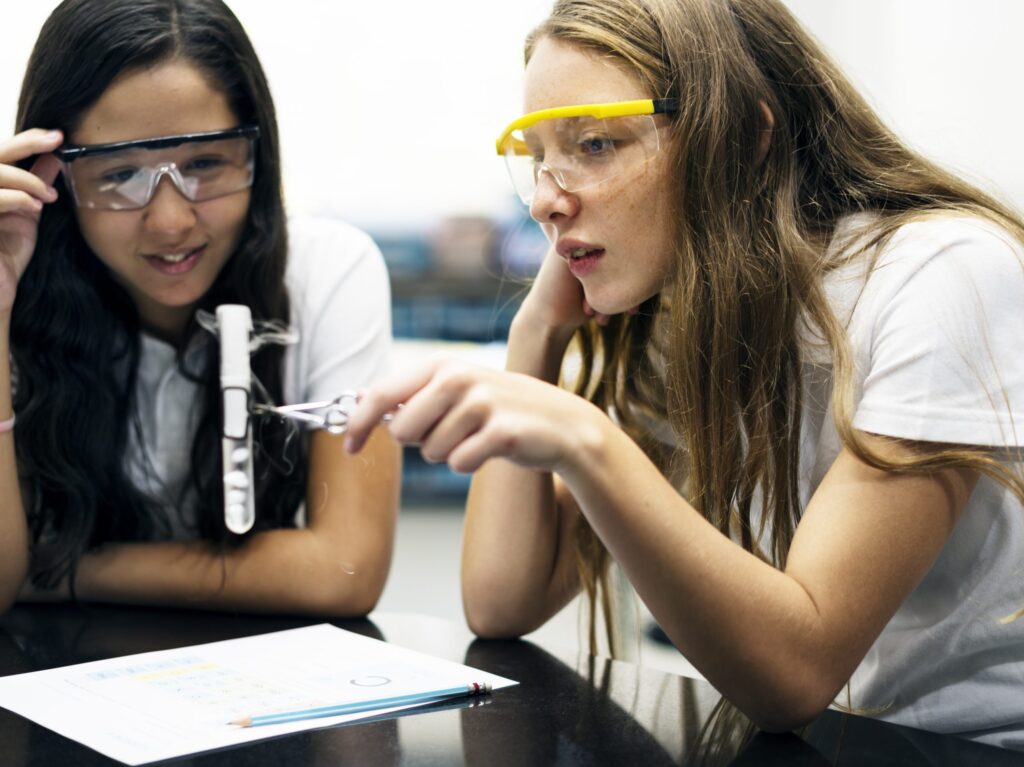

Now this represents a real opportunity for science teachers. A lot of bad science can be exposed by applying concepts that are covered in secondary school science. Despite what some people might say, you don’t absorb water into your body by holding it in your mouth, you can’t stimulate your carotid arteries by gently massaging your chest and the interlocking of the fingers of both hands doesn’t set up a circuit around which positive energy may flow. There is, however, real opportunity in science lessons by getting pupils to sort out the good science from the bad. It gives them a chance to use their understanding to evaluate assertions and to suggest why some ideas are better founded than others.

Eight of the ideas from the “Bad Science” book have been turned into lessons for pupils in secondary schools. These are being incorporated in the new Collins GCSE Science pupil books, but the lesson plans and resources are available for free download from this website. Furthermore, two of the lessons have been filmed at Humphry Davy School in Penzance to show how the teacher presented the ideas and how the pupils responded. We’ve also interviewed Ben Goldacre about the ideas in the book; the streamed videos are accessible from this website too.

The pupils’ response was tremendous. Placing young people in the role of “science detectives” provides them with an effective point of contact between the science they study in school and ideas they come across in the wider world. They know that people are trying to sell them things and they know the claims don’t always add up. Bad Science doesn’t make people more cynical; it shows them that science can be used to discriminate between the good and the bad.

Finally, an apology to people peddling pills, potions and poppycock who find their wares and claims scrutinised by teenagers with a keen eye for all things dodgy. No, actually, apology withdrawn. They had it coming.

Ed Walsh, Science Advisor with Cornwall Learning.