Black people have played key roles in shaping British history for centuries, but all too often their stories and contributions have been forgotten or overlooked. To mark Local History Month, we are highlighting some of the incredible people included in our Black British History KS3 Teacher Resource Pack who have played an essential role in shaping local and national history.

Asquith Xavier – City of Westminster

Asquith Xavier (1920–80) was born in Dominica where he worked as a police officer and spent some time in the army. He moved to Britain as part of the Windrush generation and settled in Paddington, west London, and found work as a porter and then a guard at Marylebone depot.

In 1966, the Marylebone main line was closed and guards were no longer needed, so Xavier applied for a job at Euston station. He received a letter informing him that his application had been rejected because an unofficial ‘colour bar’ was in operation at Euston and other stations, which meant management at Euston did not want Black people in roles that required face-to-face interaction with customers.

Xavier refused to accept this racial discrimination and took his case to the National Union of Railwaymen. The Branch Secretary and two local MPs brought the case to the attention of the Transport Secretary, Barbara Castle. This government intervention and union protest put pressure on British Rail to change its policy and in August 1966, Xavier started work as a guard at Euston station. He was the first Black person to do so and faced so much abuse that it caused a decline in his health. There is a plaque in Euston station in his honour.

Celestine Edwards – Sunderland, Tyne and Wear

Celestine Edwards was born on the island of Dominica in 1857. After stowing away on a French ship at the age of 12 and sailing around the world while working on various vessels, he settled in Britain.

He first lived in Edinburgh, working as a labourer, and then in Sunderland, where he worked as an insurance agent. As a committed Methodist and supporter of temperance, he gave many passionate speeches around Sunderland, including on race. He later moved to London and began to campaign against racism and prejudice, giving speeches across the country. While in London, Edwards studied theology at King’s College and attended the London Hospital as a medical student.

In 1891, he published the story of a former enslaved person from Canada, and in the next two years he founded a Christian weekly paper, which he used to express his antiracist views and his criticism of empires. He is thought to have been the first Black editor in Britain.

Dzagbele Matilda Asante – London Borough of Brent

Dzagbele Matilda Asante was born into a well-connected, affluent family in the British colony in West Africa known as Gold Coast (modern Ghana). Her brothers came to the UK to study law and medicine, and Asante joined them in 1947, successfully applying for a place as a trainee nurse at a hospital in north-west London. She started her three-year training course during the period that the NHS was first established, and before the majority of nursing recruits from the Caribbean arrived.

After completing her training, Asante moved to a hospital in north London, where she trained as a midwife and then later qualified as a health visitor. She and her fellow nurses often encountered racism, with some patients refusing to be cared for by an ‘African’. There was also tension between the nursing recruits from the Caribbean and those, like Asante, from African countries such as Ghana, Sierra Leone and Kenya. Those from the Caribbean were disparaging about the appearance of their African colleagues, but Asante worked hard to challenge some of the lazy stereotypes that existed. After her time in London, she returned to her native country, which secured its independence from British rule in 1957. There, Asante continued to work in a senior role in healthcare.

Francis Barber – Lichfield, Staffordshire

Francis Barber was born on a sugar plantation in Jamaica. In 1749, at the age of around eight, he was brought to Yorkshire by plantation owner Colonel Richard Bathurst, who ‘loaned’ him to the household of Samuel Johnson. When Bathurst died in 1756, he left Barber a small legacy of £12 (around £2,800 in today’s money), which gave Barber the freedom to leave Johnson’s household.

Barber went to work as an assistant to an apothecary in the Cheapside area of London. After two years there he left to become a sailor. It is unclear whether this was voluntary or forced (there were incidents of Black Britons being captured in port cities and forced to work aboard ships in various roles). The conditions he endured on the ship were horrific, but the continued relationship he had with Johnson helped secure his release. Johnson paid for Barber to continue his education, and Barber became Johnson’s manservant, secretary and companion. David Olusoga has suggested that the friendship between Barber and Johnson was a marked exception to the exploitative relationships typically founded on the enslavement of African people.

Upon his death Johnson left Barber an inheritance of £70 a year and expressed a wish that Barber should relocate to Johnson’s original hometown of Lichfield in Staffordshire. Barber honoured this wish, and he and his wife set up a school there. It is thought that Barber may have been the first Black school teacher in Britain.

George Africanus – Nottingham, Nottinghamshire

Born in Sierra Leone, George Africanus (1763–1834) was brought to England at the age of three and enslaved with the wealthy Molineux family in Wolverhampton. Unfortunately, we do not know the name he was given at birth as many enslaved people were forbidden to keep their birth name. The name George John Scipio Africanus was given to him by the Molineux family, who taught him how to read and write. He took up an apprenticeship within the family business, and at the age of 21 George Africanus seems to have won his freedom.

George Africanus moved to Nottingham in 1784 to work as a brass founder. Trade directories from the city show that he also worked as a waiter and a labourer. He met his wife Esther and together they set up a business similar to an employment agency. The Africanus’ Register of Servants proved to be extremely successful and by 1829, George Africanus became a ‘freeholder’, which meant that he was able to own his family home, business premises and accommodation that could be rented out. Being a freeholder also meant that he was eligible to vote. He is recognised as Nottingham’s first Black entrepreneur.

Ignatius Sancho – City of Westminster

Ignatius Sancho was born in 1729 aboard a ship transporting enslaved people from Guinea to the Spanish Caribbean. His mother died shortly after his birth and his father died by suicide to escape the enslavement he was facing. When he was two years old, Sancho was taken to Britain and given to three sisters who lived in Greenwich, London, to be raised as a servant.

As a young man, Sancho struck up a friendship with the Duke of Montagu and his family. He worked as the Duchess’s butler for nearly 20 years until her death in 1751, and then as valet to her son until 1773. When he died, the Duke left Sancho a small inheritance.

Using this money, Sancho opened a grocery shop in Westminster. The venture was so successful that he gained financial independence. With financial independence came the right to vote, and in 1774 Sancho became the first person of African descent to vote in a British general election.

When Sancho died in 1780 he became the first known person of African descent to have an obituary published in British newspapers. His memoir, Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, was published in 1782, making him one of the first people of African descent to have his work published in England. Sancho’s letters proved invaluable to the abolitionist cause.

Joseph Emidy – Truro, Cornwall

Joseph Emidy (1775–1835) was born in West Africa. He was captured on the Guinea Coast as a child by the Portuguese. His impressive talent on the violin won him a place in the Lisbon Opera Orchestra. However, this ‘freedom’ ended abruptly when an admiral in the British Navy, Sir Edward Pellew, saw him play. Emidy was kidnapped and enslaved again on-board Pellew’s ship.

In 1799, Emidy was discharged at Falmouth. He began working as a teacher and violinist, moving to Truro in Cornwall in 1815 where Emidy really made his name as a musician and became an influential figure. There is a memorial stone to Emidy in Kenwyn churchyard in Truro, but unfortunately none of his music has survived.

Mary Prince – London Borough of Islington

Mary Prince was born into slavery in 1788, in the British colony of Bermuda. In her early life she was sold to a series of brutal slaveholders, at whose hands she experienced the true horrors of such a life. Prince eventually found herself in Antigua, owned by the Wood family. In 1826, she married Daniel James, a carpenter who had bought his own freedom – although she was punished severely for marrying without first seeking permission from the Woods family. In 1828, while accompanying the family on a visit to London, Prince escaped. Slavery was no longer legal in Britain, so Prince was officially a free woman while she remained in the country; however, this meant that she was unable to return to her husband, who had been left behind in Antigua when the family travelled to England.

Seeking help from groups linked to the abolitionist movement, Prince was given warm clothes, money and assistance in finding paid work. In November 1828, she met Thomas Pringle – an abolitionist writer and Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society – and moved into his home and began working for him as a domestic servant. During this time, and with Pringle’s help, she wrote her autobiography, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself, which was published in 1831. The book drew attention to the terrible conditions in which enslaved people were still living and working in the plantations, despite the abolition of the transatlantic trade of enslaved people more than 20 years earlier.

While many of her supporters were middle-class women, few saw her as an equal, and refused to invite her to their various society functions. But Pringle’s publication of her work, and his use of it to pressure parliament, ensured that Prince became known as an influential abolitionist and as the first Black woman to publish an account of her life and experiences as an enslaved person in the Americas.

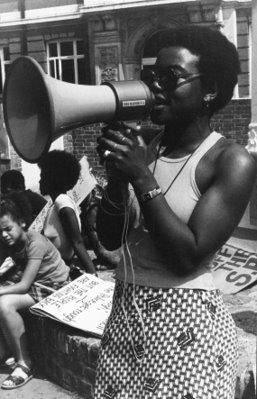

Olive Morris – Manchester, Greater Manchester

Olive Morris dedicated much of her life to tackling the problems of poverty and racism that existed in Britain. Morris was born in Jamaica in 1952 but moved to Britain in 1961, aged nine. Even though she left school with no qualifications, she attended night classes before graduating from Manchester University with a degree in Social Sciences. Morris was committed to fighting for women’s rights and Black rights, and she co-founded and worked with various organisations, including the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent, the Brixton Black Women’s Group, Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative, Manchester Black Women’s Mutual Aid Group and the Brixton Law Centre.

In 1972, Morris helped to organise a protest after two young children were killed in a house fire that started when portable heaters were knocked over. The children were living in a council house (housing provided by local governments for people on low incomes) and Morris and other demonstrators, including local children, held a rally outside local government offices to demand better public facilities. The council workers inside threatened to call the police, so Morris instructed the protesting crowd to go home. However, she sent the children into the building, knowing that the police would not arrest them. The head of the housing department came outside and promised to look into what had happened. Central heating was soon installed in the housing where the tragic deaths had occurred.

The same year, Morris began squatting in uninhabited buildings. This was not a crime – in fact, if squatters stayed in empty buildings for long enough, they could claim the right to stay there. Through this action, Morris and her fellow activists drew attention to the fact that many properties stood vacant while thousands of people were without adequate housing.

A vacant flat above a laundrette in south London that Morris and her friend, Liz Obi, squatted in was turned into a bookshop which sold literature that supported the struggle for equality. This became a popular meeting place for the Black community. It was here that protest groups like Black People Against State Harassment met to organise their response to continued racial discrimination and prejudice.

Just a few years later, Morris developed cancer. She died in 1979, aged just 27. She had refused to submit to racial oppression and had worked tirelessly to protect the rights of Black people, and Black women in particular. In Lambeth, London, a council building was named after her. Olive Morris House was, however, demolished in November 2020. This fact has been viewed by many as an example of her legacy and work being forgotten.

Sir Wilfred Wood – London Borough of Croydon

Sir Wilfred Wood was born in Barbados in 1936. After completing his theological studies, he was ordained as a deacon in 1962. He was posted to a diocese in London and served in a parish in Shepherd’s Bush. Wood was eventually made Bishop of Croydon in 1985 – the first Black Bishop in the Church of England.

Wood took a keen interest in race relations, and worked hard to promote social justice and to combat racial inequality. He worked on various commissions to try to improve the criminal justice system and deal with issues of urban poverty. He was the moderator of the World Council of Churches Programme to Combat Racism and protested against the apartheid regime in South Africa. Bishop Wood spoke out against the praise that was given to Enoch Powell on his death. Wood also spoke out about the treatment of asylum seekers, arguing that Britain should provide a refuge for people fleeing persecution and oppression.

In 2000, the late Queen Elizabeth II appointed him Knight of St Andrew (Order of Barbados) for his contribution to race relations in the UK and for his work to support the welfare of the Caribbean community in Britain.

Find out more about bringing other influential Black British figures into your classroom with Black British History KS3 Teacher Resource Pack, a customisable teacher pack to help you shine a light on Black British history.

You might also be interested in

Black history is British history

Dr Simon Henderson and Teni Oladehin, authors of the teacher pack discussing how you can integrate Black British history into your KS3 curriculum.