O2, H2O, CO2 – symbols and formulae ‘are’ chemistry to many people and some are used in ads and company logos which have little to do with chemistry. It is two hundred years (or thereabouts) since the combination of capital and lower case letters and numbers was first used to represent elements, compounds, atoms and molecules and in chemical equations.

Symbols have a long history in chemistry. In the Middle Ages the alchemists, who devised many of the processes we use today, used word and picture symbols instead of the name of substances. For instance, gold was often represented by the Sun, or a great king, or a lion. These symbols may have been used to help the alchemist recall the recipe for the process or to hide the real substances and processes from people not permitted to know the secrets and rituals of alchemy.

Alchemy and astrology shared many ideas. The seven metals known before modern chemistry were each associated with one of the planets and shared the symbols. Non-metals were also given symbols.

[alchemical symbols for metals and none-metals e.g. gold, iron, sulfur, as on the RSC website http://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/alchemy ]

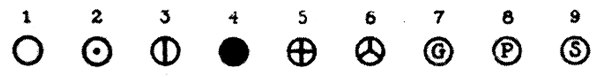

Modern chemistry came into being in the late eighteenth century after the Frenchman, Antoine Lavoisier, named oxygen and gave new names to other elements and compounds. In 1808, John Dalton, who worked in Manchester, published his book A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Dalton set out his idea that elements were made up of atoms. He said that all the atoms of an element were tiny solid balls with the same mass and that the atoms of different elements differed in their atomic masses. He also said that atoms could join together to form compounds. Dalton illustrated his ideas with diagrams which used a new system of symbols for each of the elements which were known. Every symbol was based on a circle representing an atom.

Oxygen hydrogen nitrogen carbon sulfur phosphorus gold platinum silver

[Dalton’s atomic symbols http://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/chemical_symbols.php ]

Earlier symbols just stood in for the name of the substance but Dalton intended his symbols to represent one atom of the element. Unfortunately they were difficult to remember and there was another problem. The start of the nineteenth century saw a huge growth in chemical publications – books and journals. Printers found Dalton’s symbols expensive and time-consuming because each element had to have a special piece of type cut for the printing press. It was Jöns Jacob Berzelius who provided the solution.

Berzelius was born in Sweden in 1779. In 1796 he went to the University of Uppsala but because of a shortage of money he did not complete a degree in medicine until 1802. In the gaps in his studies he performed his own experiments in chemistry. After graduating he assisted a mining chemist where he developed his skills at analysing substances and separating elements. In 1807 he was appointed as a professor at the School of Surgery in Stockholm where he was able to devote his life to chemistry. He was a very methodical and careful scientist and with his assistants, was the discoverer of many new elements including lithium, vanadium and selenium. Perhaps more importantly, he measured the atomic masses of all the known elements and achieved much greater accuracy than Dalton or other contemporaries. He supported Dalton’s atomic theory and wrote articles and textbooks which spread the ideas. He realised that a simpler way of representing atoms was needed and he described his system in an essay published in 1814 in a journal, the Annals of Philosophy. Berzelius used simple letters and punctuation marks that all printers had available. He suggested using the capital first letter of the element’s name or, if necessary, two letters as the symbol of the element. The letters were taken from the Latin form of the name so the symbol of iron is Fe from the Latin “ferrum”. When writing the formula of a compound Berzelius used small numbers for the number of atoms, but he placed them above the symbol, e.g. sulfur dioxide SO2. As many compounds contained oxygen Berzelius suggested an even quicker way of writing the formula, replacing the oxygen atoms with dots. Thus calcium sulfate (CaSO4) became

. …

CaS

Berzelius corresponded with chemists across Europe and many visited Stockholm to be taught by him. Other chemists realised how useful Berzelius’s symbols could be although Berzelius himself did not make much use of them. Dalton preferred his own symbols and never used the new system. Berzelius continued with his research until his death in 1848.

Various versions of Berzelius’ symbols were used until the system we use today became common. First to go were his dot formulas and the numbers moved to the bottom in the 1830s. The symbols used in formulas and equations became the language of chemistry. They enabled chemists across the world to communicate whatever their spoken language. Also, when used in formulas and equations chemists were able to visualise reactions and imagine atoms combining to form molecules. Two hundred years after Berzelius publicised his idea symbols are still one of a chemist’s most important tools.

Activities.

- Why do you think gold was often represented by a king or emperor in alchemical drawings?

- The seven metals known in the Middle Ages were copper, gold, iron, lead, mercury, silver, tin. Suggest why these metals were used long before other metals were discovered.

- Draw the following formulas using Dalton’s symbols. H2O CH4 Ag2S H2SO4 CS2

- Name and give the symbols of the elements that have just a capital letter as their symbol.

- What are the English names of the elements that have the following symbols based on their Latin names? Au Sn Na Pb W

- a) Write a “dot formula” for compounds carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and sodium nitrate (b) Why do you think the Berzelius’ idea of dot formulas didn’t catch on? Why did most chemists prefer Berzelius’s symbols to Dalton’s?

- Suggest reasons why Berzelius’s system of symbols was important to the development of chemistry.

- Find out more about Berzelius’ life and work.

Reference:

- J.J. Berzelius. Essay on the Cause of Chemical Proportions, and on Some Circumstances Relating to Them: Together with a Short and Easy Method of Expressing Them. Annals of Philosophy 2, 443-454 (1813), 3, 51-2, 93-106, 244-255, 353-364 (1814) [from Henry M. Leicester & Herbert S. Klickstein, eds., A Source Book in Chemistry, 1400-1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1952)]

http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/berzelius.html

2 Oxford Dictionary of Scientists, pub. OUP

3 A History of Chemistry, vol 4, J.R.Partington, pub. Macmillan

Peter Ellis