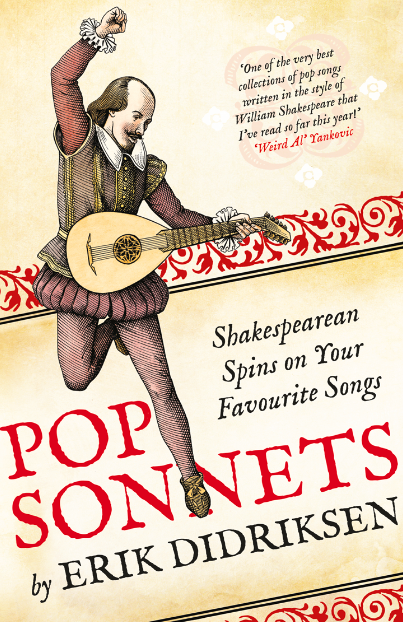

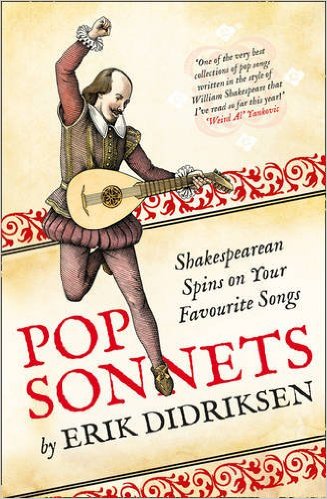

Download the accompanying lesson plan by Erik Didriksen here.

Download the accompanying lesson plan by Erik Didriksen here.

Here’s a thought experiment: what current books will be read in the future? What movies and TV shows will they watch a century from now? What songs from 2015 will they listen to in 2215? I don’t mean this in an academic or archival sense; I’m talking about the works people pick up and enjoy on their own — the way Pride and Prejudice and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes still grip us despite being over a century old.

I can imagine a wide range of answers. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Harry Potter, Twilight, or The Girl on the Train among the books. While you may not love them all, it’s hard to deny their enormous success. Now imagine them four centuries from now, among all the books written and enjoyed over that time. What tiny percentage of them will be remembered, much less enjoyed? Think about it in reverse: how many sixteenth-century writers can most people name, much less casually reference?

The sole exception is William Shakespeare, who is not just remembered but culturally omnipresent. Taylor Swift name-drops a four-hundred-year-old play in the chorus of “Love Story,” and everyone knows exactly what she’s talking about. Grade school kids can confidently finish “To be or not to be?” with “That is the question.”

So if Shakespeare’s still so wildly popular, how can so many people find him unapproachable?

There are a few obstacles to our modern enjoyment of the Bard, but the biggest ones are self-imposed. People often think of Shakespeare as unrelatable and dull, but the fault, dear readers, is not in his work, but in ourselves. We tend to consume his work the wrong way; his words were not meant to be quietly read, but heard on stage. So many of the language barriers we face fall away when his plays are dramatically performed. It’s a crime that so many people only read his work and never see it acted out. Reading his plays aloud in class is certainly an improvement, but it’s not a complete substitute, particularly if they’re reading it cold. When performed at their best, plays are interpreted by actors who’ve internalized and grappled with a work long before they see an audience.

Even when we watch Shakespeare’s plays, though, we approach it in the wrong context. We treat him far too reverentially — his plays were never intended to be viewed like a church service. They were written for a less dignified stage. Audiences would talk over performances if they were bored, or would shout to characters when they got lost in the action. It was more like a rock concert than a West End show — and fittingly so, because the material is often just as over-the-top and bawdy. There’s enough crude humor in Shakespeare’s plays to fill a few Will Ferrell movies; we just don’t catch a lot of the jokes due to shifts in language. Changes in common vocabulary and even pronunciation leave us in the dark when his audiences would have been left in stitches. Others go by simply because we think we’re watching something too dignified to make such jokes. (Shortly after I graduated, my high school staged Twelfth Night — and cut a line from Act II, Scene V once they realized Malvolio was spelling out a dirty word!)

These barriers are entirely of our own making. Personally, I became more motivated to get through the language difficulties once I knew there were dirty jokes and stories worthy of Game of Thrones on the other side. His work becomes accessible when we stop holding him up as the pinnacle of “high art” and start thinking him as the Coen Brothers or Tarantino of his day. For too long we’ve confused our difficulty with his language with sterility; once we recognize his work as the media we already consume, it becomes relatable and approachable.

Yes, we still do need to wrestle with the linguistic obstacles, but unfamiliar language doesn’t need to prohibit our enjoyment — or at least our basic understanding. The deliberately unfamiliar vocabulary of Orwell’s 1984 and Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange hasn’t prevented us from enjoying them. Even pop music requires vocabulary lessons these days. The user-annotated lyric site Rap Genius gained popularity because people want to understand the obscure phrases in their favorite songs. (I admit their write-up of Fetty Wap’s “Trap Queen” expanded my vocabulary as much as any Shakespearean soliloquy.)

And once we’ve cleared that hurdle, we’re treated to a world of vivid characters and gripping tales. We can exult in beautiful language. We can explore the structure of effective and economical storytelling. We can better understand our own cultural landscape, and learn how we might construct our own stories that live on long into the future.

Written by Erik Didriksen, author of Pop Sonnets. Follow Erik Didriksen on twitter!