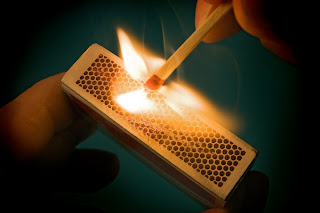

It was WB Yeats who told us that, “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” It’s a quote I’ve long admired and to me it sums up the reason why I went into teaching. It’s something I’ve always tried to remember when planning lessons and delivering them and when building a rapport with students. Looking back, this approach has been quite successful (this can be supported by exam result data – there, I am being ‘accountable’ therefore a good teacher) – although I would argue this is a common sense approach.

If students want to be in your lesson, they know why they are studying the subject and they know what they are getting out of the subject they will, and ten years of experience tells me this, for the most part, be enthusiastic and keen to learn. Sadly, in the ‘League Table culture’ in which we work, I’m worried we’re losing this a little bit. Students increasingly seem to ‘just want to know what they need to pass the exam’ and nothing else – and the pressure we are under as teachers to meet Gosplan’s targets means we often, and I say this reluctantly, do just that. We spoon feed, and sometimes there are other factors in play too. There is often political pressure, for example when an Academy has to prove it is successful not for its pupils’ sake, but for the sake of saving a politician’s bacon. Students can therefore pass exams – but are they better educated? Politicians can boast that on their watch exam results went up 63%… but what disappoints them is that education is simply not measurable.

Anyway, let’s keep politics out of education (I wish MPs would just ‘let the teachers be free to teach’ as I believe they promised)… in part contradiction of Yeats I would argue that of course we need some ‘filling of the pail.’ Without any historical knowledge at all students are going to struggle to get any idea of the past – facts, dates, battles and people all help students get a sense of historical context and why things happened. Chronological facts helps students string things together, link events and see that history is not packaged into nice little compartments and, taught properly, it will help them see things did actually happen between the Romans, Tudors and the Industrial Revolution!

In short, we need knowledge and facts, but not just knowledge and certainly not a curriculum based around Core Knowledge – facts we all must know. History has fought hard to move away from being just a memory test requiring factual recall of dates in order for someone to be ‘good at it’. Some good news coming from the government – surprisingly, it would seem, as all that seems to come out of Westminster is a continual bemoaning and belittling of our profession – is that History is soon to become compulsory up to the age of 16. Three cheers all round – Mr Gove has finally got something right! This should hopefully counter the worrying trend of less History being taught. I was a little disappointed to find out that the school I taught at for six years before moving abroad, building up both the GCSE and A-Level cohorts considerably, now offers a three year Key Stage 4. This problem is heightened by the three-tier system they have so students arrive from Middle School and have little more than a week before they decide their options – this has led to very small numbers taking the subject as we don’t have Year 9 with every student to develop skills and interest. We hope that making the subject compulsory will mean decreasing numbers of students taking the subject is merely a blip, but even then we can’t get complacent. We still need to light the fire Yeats talked of.

So what about the lighting of the fire? How do we do it? Having just helped out our English department with some GCSE tuition with some very disaffected Year 10s and 11s I am aware of the difficulties a compulsory subject faces. ‘When am I ever going to need to know about Macbeth?’, as I was asked many times, could soon become ‘When am I ever going to need to know about Abraham Darby?’ if we do not approach it right. I’ve highlighted earlier the need to always let the students know why they are doing what they are doing, how relevant it is and the skills they are getting out of it. Something else that has worked for me is the mantra ‘teach as you would like to be taught.’ All teachers have different styles and whilst we seem to be constantly observed and scrutinised it is important to remember that you have to teach your way. This way you feel more comfortable in front of the class. Thorough lesson planning will mean you know the different needs of the learners in front of you and you can adapt accordingly but you need to lead, to inspire, to be a good role model and to show the students that education is not just about passing exams or that GCSE History merely leads to becoming a museum curator or librarian – not that there is of course wrong with either of those professions. One particularly able student of mine at the international school I taught at used to ironically shout out “but that’s not on the syllabus we can’t discuss that” every time one of our IB History lessons drifted off topic. If a debate is going off topic then let it – if the students are engaged and thinking and learning from one another, keep going – that is education. That is inspiring students to think for themselves. That is lighting their fires.

After one whole staff meeting where we’d just been told the expectations for forthcoming observations, I remember one old cynic chirping up at the back “Oh, so we’re supposed to be entertainers now are we?” Cue much laughter, but the fact remains that if we’re doing our job well then well, yes we are but that doesn’t mean role plays, field trips and TV clips featuring blood and guts. Showing warmth, humour and appearing human through a variety of anecdotes have worked for me. You may not look forward to your double with 8Y on a Friday afternoon – we all have an 8Y – but you always have to show the passion and yes, it’s not easy when you have to discuss proportional representation in the Weimar Republic for the fifteenth time, but it is a relatively simple solution. Showing the passion for your subject rubs off on your students and of all the possible ways of lighting the fires Yeats dreamed of, I’ve found this is the easiest way to light them.