In today’s blog, I will consider how using shared creative writing in the classroom can help students to improve their analysis of the writer’s intended effect.

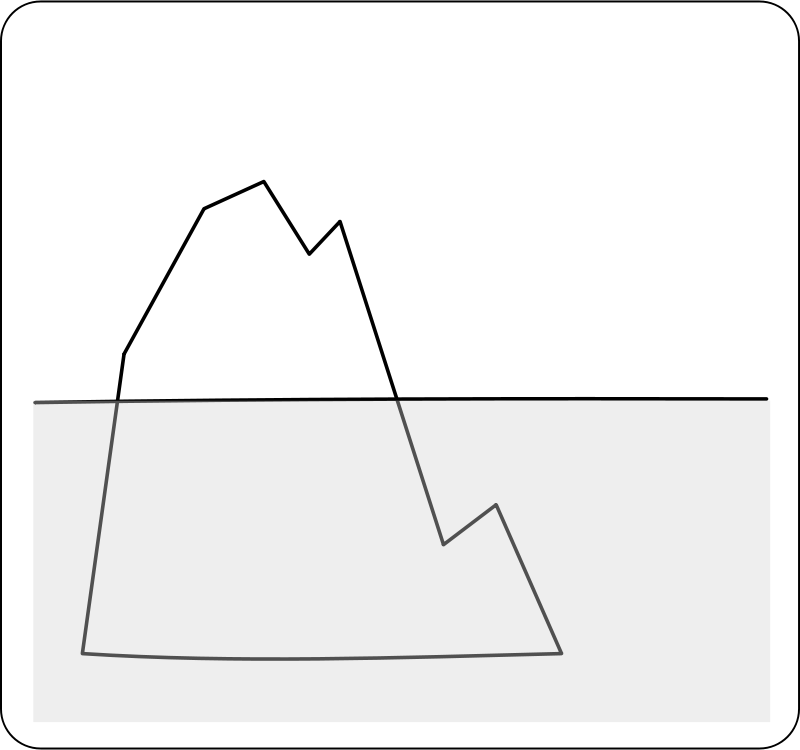

In my last blog, I suggested the using the analogy of Icebergs to improve students’ understanding of the layers of meaning in language. In their most recent timed assessment, my GCSE students did brilliantly at the IC of the ICE acronym, commenting on the Implicit meaning (I) and Connotations (C) of word choices with great gusto. However, they are still struggling with the E, the writer’s intended effect, which leads to some rather wobbly and precarious icebergs!

Subsequently, after some discussion with a colleague (and much tearing of hair out), we decided to turn our lessons on their head and go back to front with our teaching of reading.

The planned outcome of our lesson was to analyse Steinbeck’s intended effect in the opening of ‘Of Mice and Men’. We began by displaying a picture of a murky looking pool. I asked students to create a word bank for a ‘sinister pool.’ We then used their words to construct a piece of creative writing. I thought out loud, while writing, asking the students to think of phrases which created the impression of a ‘sinister pool’, e.g. ‘The weeds grasped the bank like outstretched fingers.’

The process of writing and editing our description helped the students to understand that writers do actually make choices when writing and how they might go about it. After we completed our paragraph, I asked students to then answer an exam-style question about the effect of words, which describe nature in the paragraph. I was astounded by how their responses immediately became more focused and insightful.

This method was then be repeated, with students looking at more pictures, writing their own paragraphs and marking each other’s work. The peer assessment was very powerful with the ‘writers’ marking the ‘readers” responses and then judging whether the readers had adequately (a) identified and (b) explained their intended effect.

Only after this process did we look at the ‘real’ piece of writing, the Steinbeck extract. We kept it small, focussing on the opening paragraph. Once we had read it, I asked the students to identify the impression we are given of the pool and which words helped us to understand this. By comparing it to their own writing, the students were much more quickly able to engage with the idea of the description signifying something other than just a literal depiction of ‘a pond and some big mountains.’

This method is so successful because it forces students to engage with idea that the words used by writers, including themselves, can be planned, deliberate and meaningful. I will definitely be using it again with both KS3 and KS4 and hopefully the E of ICE will become the layer which stabilises the whole iceberg.

Naomi Hursthouse

Naomi Hursthouse has been teaching in West Sussex for nine years. She has worked as an Advanced Skills Teacher for four years and is currently Head of English at Westergate Community School. She has worked as an examiner for AQA for nine years and has been writing articles and blogs about teaching for Collins Freedom to Teach since 2009. She was born in Dumbarton, Scotland but moved down to the South Coast of England for some sunshine ten years ago. This year, she has finally found it.

Have you tried out Naomi’s iceberg analogy in the classroom yet? Or have you got any tricks of your own to boost students’ analysis skills? Share your ideas below!